ESG: Extreme Shortage Guaranteed?

Macro Update: Sri Lanka’s Food Crisis Is a Sign of What's to Come

Sri Lanka is often referred to as “The Pearl of the Indian Ocean.”

The country is adorned with an array of magnificent wonders – culture, history, people, geology, flora, and fauna.

I couldn't agree more with its nickname. Back in 2017 when I visited this magnificent country, I had an amazing time thanks to its fantastic food, great people, rich culture and heritage, diverse wildlife, and stunning landscape. This literal paradise is often overlooked and underrated as a vacation destination.

But that changed in 2022.

73.7%.

That is not the free throw average of LeBron James, but it is the year-over-year (YOY) change in inflation for Sri Lanka in September of 2022, which is the highest on record for the country.

In fact, since the end of 2021, Sri Lanka has had one of the highest inflation rates in the world.

And it looks something like this.

For the theme park fans out there, the chart looks like the beginning of an exciting, adrenaline-pumping rollercoaster ride. But for Sri Lankans, it’s been a nightmare.

This inflation led to massive anti-government protests that pushed Sri Lanka under the global spotlight. Then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa went into exile, and the country is still trying to climb out of its economic woes.

Simply speaking, Sri Lanka’s runaway inflation was caused by energy and food shortages.

Sri Lanka is not an energy producer. Hence, that shortage is understandable. With meteoric energy prices in 2022, affordability was and still is an issue for countries without deep access to foreign reserves. Many cannot afford to buy energy when prices were going up while their own domestic currencies depreciated in value.

The causes behind the food shortages, however, are a real head-scratcher.

Once the largest rice exporter in the world until 2019, Sri Lanka resorted to importing rice for domestic consumption in 2020 and 2021.

The reversal is quite astonishing.

What triggered the sudden sharp drop in rice production?

It was a key policy change that’s gaining momentum in other countries as well. And it could lead to more food shortages (and more waves of higher inflation) across the world, if governments don’t understand how it plunged Sri Lanka into chaos.

Let’s plow right in.

The Nutrient for Nutrients

It all starts with chemical fertilizer.

So first, let’s unpack the impact of fertilizer use.

Fertilizers are the most vital component for farming aside from weather anomalies.

The world population never would have reached nearly 8 billion without the use of chemical fertilizers.

Let’s bring back the chart that we used in the inflation update from earlier this month.

It shows the global consumption of fertilizer from 1850-2015, especially nitrogen fertilizer.

If we overlay the global population growth over the chart above, we can see that they’re highly correlated in the chart below.

The growth of the global population simply would not have been possible without chemical fertilizer.

It is an understatement to say chemical fertilizer is pivotal to providing and ensuring an ample global food supply.

Without it, we would not have been able to sustain the past century’s population growth. And we would not be able to grow enough food to feed everyone on the planet.

Chemical fertilizer, along with chemical agents such as pesticides and herbicides, are what enabled global agriculture to increase crop yield exponentially to support the booming population expansion since the 1950s.

And it is these chemical wonders that allowed agriculture in nations such as Sri Lanka to flourish. Not only is its crop yield enough to feed its own population, but the surplus can be exported to boost GDP, improve the domestic economy, and accumulate foreign reserves.

But that was Sri Lanka pre-2020.

Let’s take a look at Sri Lanka now.

There’s Trouble in Paradise

Our 2022 post on the Jones Act explained that the causes for inflation are not just limited to external factors like the Ukraine War. Government policies are also the main drivers of inflationary pressure.

The agriculture harvest shortfall in Sri Lanka is the prime example of failed government policy.

It all started with an Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) mandate from the government.

In 2019, the now-exiled President Gotabaya Rajapaksa promised to transition to organic agriculture. True to his words, in April 2021, Sri Lanka imposed a nationwide ban on fertilizers and pesticides and forced the country’s 2 million farmers to go organic. No chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides were allowed.

And instead of rolling the measures in several stages to counterbalance and absorb the systemic shocks and shortages as a result from the new measures, the government pulled the plug and stopped the use of all chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides all at once.

Sri Lanka was the world’s No. 1 rice exporter in 2019. It constituted 41.6% of the world’s entire rice exports.

But in 2022, Sri Lanka had to import rice from Japan.

One might wonder if the drop in production was due to less acreage planted courtesy of COVID-19 pandemic. That is not the case, however.

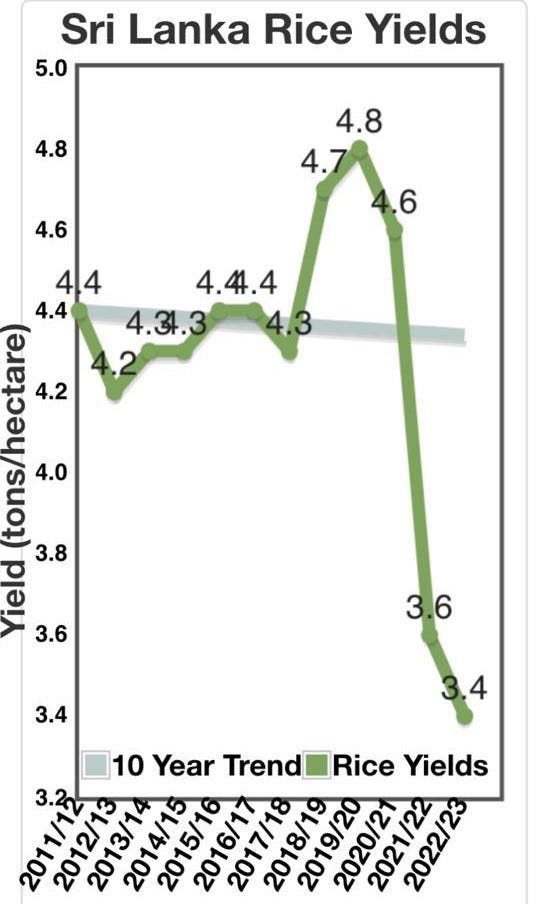

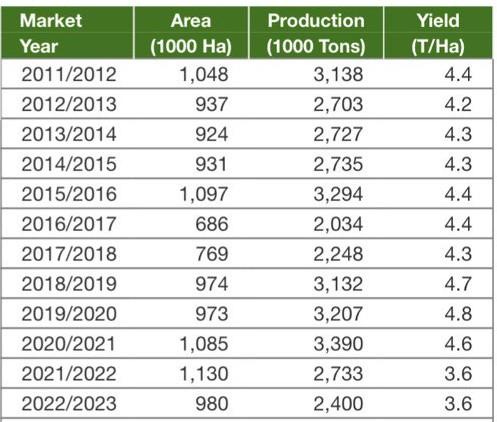

Below, we have two charts from the USDA that highlight how yield per hectare in Sri Lanka has decreased by more than a ton per hectare since the ban on chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

That is a 26% drop in yield per hectare.

Is it a coincidence?

No, not likely.

The absence of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides wreaked havoc on Sri Lanka’s food supply.

Rice is also one of the crops that requires nitrogen fertilizer more than other types of fertilizer to cultivate.

To compound the matter worse, it is not just rice. All other major agricultural exports from Sri Lanka have taken a hit because of the low yields caused by the ban. Tea and cinnamon are the two largest export items for Sri Lanka. Their farmers are also suffering.

Lower exports lead to higher imports, a larger trading deficit, and smaller foreign reserves. A recipe for a perfect storm for a place like Sri Lanka.

But what does ESG have to do with fertilizer and food supply?

ESG Is Going to Change the World – But for the Better?

The Environmental, Social, and Governance movement, commonly known as ESG, is and will most likely be a main culprit for the future fertilizer shortage.

Please understand, we are not saying ESG is good or bad. We are just presenting the example of Sri Lanka to project potential scenarios of what might happen in the years to come.

But the fact is, in the eyes of ESG, chemical fertilizer is evil.

That is because chemical fertilizer is a carbon-intensive product. The production, transportation, as well as the application of chemical fertilizer and other chemical agents itself, is viewed as harmful and destructive to the environment and socially irresponsible.

Especially nitrogen-based fertilizer. Nitrogen fertilizer is a byproduct of fossil fuels and natural gas. It is not a coincidence that some of the largest nitrogen-based fertilizer producers and exporters in the world are also the largest crude and natural gas producers.

The painful sticking point for ESG is that to produce, transport, and apply one ton of nitrogen fertilizer requires an amount of energy equal to two tons of gasoline.

This goes against the grain of every fiber of ESG.

Expect ESG mandates and policies that will require tighter emission control, a reduction in the use of fossil fuels, and an increase in the carbon credit cost for fertilizer manufacturers.

This certainly will impact structural changes which translates to struggles for the supply side and inability to meet the demand in the future.

Is there a substitution for nitrogen fertilizer?

In terms of economy of scale, no.

The Inconvenient Truth

While Sri Lanka provides a glimpse of what might happen should governments around the world adopt the ESG mandate and issue/enforce policies similar to the ones in Sri Lanka, there are other potential implications.

The ESG mandate is not restricted to crop agriculture alone. Animal husbandry will be impacted as well. The farmers' protest in the Netherlands last year is a prime example.

With the shortage of fertilizer and its increased cost, we can expect farmers to switch to crops that are less fertilizer-intensive. This means there will be fewer varieties of grains, fruits, and vegetables at the market.

The removal of fertilizers and chemical agents will lead to a drop in crop yields in the future. As demonstrated by Sri Lanka, without fertilizer, crop yields craters drastically. This will certainly cause a global food shortage. Many countries that are food exporters now might reverse course just like Sri Lanka.

Further, shipping food from one global region to another global region might be deemed as carbon intensive and asked to be reduced.

Want an avocado smashed toast in Tokyo? That might not be possible anymore because shipping avocados from Mexico or Australia is too carbon intensive.

Craving a taco in Dubai? It might not happen. The tortilla is from the U.S., the tomato is from Turkey, the onion is from Egypt, and the list goes on.

Putting it all together, what does it all mean?

It means the food supply will most likely start to experience shortages. The selection and the varieties in the market will be sporadic. The volume will dwindle. We can expect to see volatile swings in the food supply.

But more importantly, it will increase prices for food.

And this means higher inflation as a result of government policy.

This is structural inflation that will be persistent – and it won't be easily resolved.

Perhaps, it is the inflation reprieve that we are seeing right now that is transitory.

Be prepared.

Yours truly,

TD

Always such clarity and simplicity in your writing. Great work! Thanks.