Jones’n for Changes

Macro Update: Why the US Congress is a culprit for inflation

The 2022 hurricane season is a busy one.

Hurricane Ian ruthlessly savaged most of Florida. Hurricane Fiona mercilessly devastated Puerto Rico.

The relief efforts for both Florida and Puerto Rico started right after the Category 4 storms moved away. But the result could not have been more different.

Florida made a speedy and immediate recovery. Puerto Rico had an entire island blackout for days afterwards with no relief in sight.

Even though there was a tanker with 300,000 barrels of diesel right off the coast that could have fueled the island’s generators, the diesel on board could not be unloaded at Puerto Rico.

Reason being is the tanker carying diesel from Texas was flying a flag of a different country.

A 102-year old ancient relic rule forbids certain tankers from docking at the port in Puerto Rico.

And because of this, it not only slowed down the relief effort for Puerto Rico, but it also made it more expensive to send aid to Puerto Rico.

This ancient relic also contributes to something we see in the headline every day; Something that makes the Federal Reserve (FED) sleepless at night: Inflation.

Everything from gasoline, natural gas, cereal, power tools, daily staples, and pretty much anything else one can think of all cost more because of it.

Let’s find out what the culprit is.

Mister Jones

Wesley Livsy Jones.

Jones was a congressman from the state of Washington from 1899 to 1909 and a Republican senator from 1909 to 1932.

On June 4, 1920, he introduced the Merchant Marine Act, also known as the Jones Act. Congress passed the law the same day, and it went into effect on June 5.

The Jones Act focuses on maritime commerce.

To be specific, the act mandated certain requirements for all goods transported between ports in the U.S., as well as ports in its island territories (Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Guam):

The goods must be transported on vessels built in the U.S.

The vessels must be owned by U.S. companies.

The vessels must be captained and crewed by U.S. citizens or permanent residents.

Coming just two years after World War I, the act was intended to protect U.S. maritime interests from foreign competition. But 102 years later, it desperately needs some modifications.

While the act insulated U.S. maritime commerce from foreign competition, it also made the industry very inefficient and cost-ineffective. This translated into higher shipping costs for U.S. residents.

And no one’s suffered more from this legislation than the residents of Puerto Rico and Hawaii.

An Invisible Tax

What do the residents of Puerto Rico and Hawaii have in common?

They have long yearned for the repeal of the Jones Act.

Puerto Rico and Hawaii get a large portion of their staple goods from the mainland U.S. By stripping the ability of foreign ships to transport these goods, the Jones Act drives up prices and increases the cost of living for both regions.

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) published a report back in 2012 outlining this problem. It found that the cost of shipping a container from an East Coast U.S. port to Puerto Rico ($3,063 USD) is twice as much as shipping it to the Dominican Republic ($1,503 USD), which is right next to Puerto Rico.

Another report from a New York-based economic consulting firm found that the Jones Act levied an additional cost of $374 USD per citizen per year in Puerto Rico.

Aside from higher prices for staple goods, energy is a main concern.

For Puerto Rico, instead of getting liquified natural gas (LNG) from Louisiana or Texas, it gets LNG from Trinidad and Tobago, the Dominican Republic, France, Algeria, and Norway, forcing cargo ships to travel a lot further. Plus, it is much more expensive to buy from margin dealers instead of directly from refineries in the U.S.

The Act was once again the focal point in Puerto Rico this past hurricane season as mentioned in the beginning of this update.

The Biden administration did finally move to temporarily waive the Jones Act before the end of September, enabling the diesel to reach Puerto Rico.

Hawaii shares the same pain.

Even though Hawaii does not have to deal with hurricanes, it relies heavily on foreign oil to power the islands, because of the Jones Act.

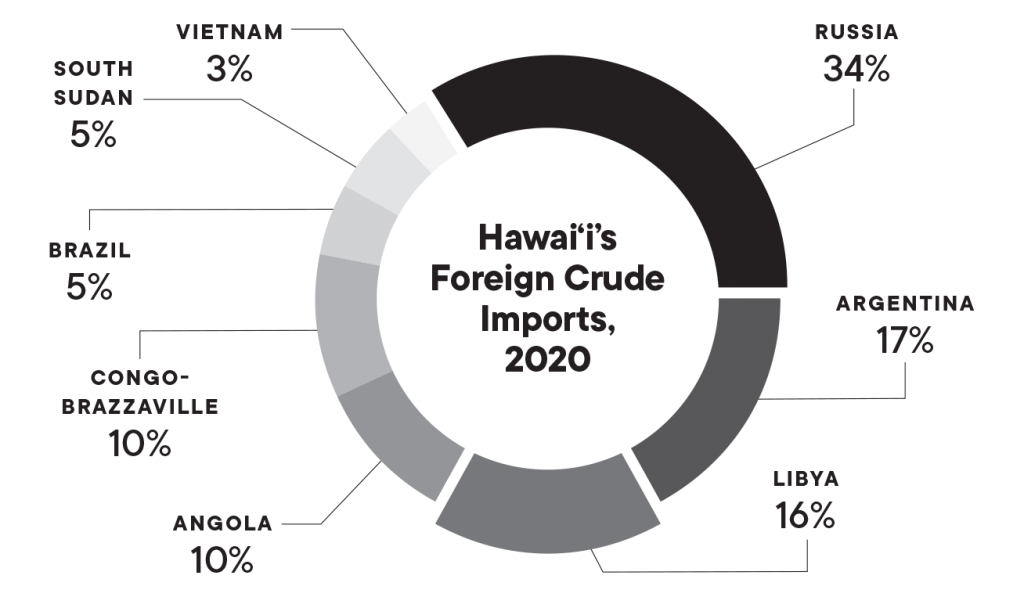

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

That is quite a long distance for crude oil to travel to get to Hawaii.

However, this is still cheaper than buying crude from the U.S. and shipping it from an American port.

The Grassroot Institute of Hawaii also did a study back in 2020, and it estimated that on average, a Hawaiian family pays an extra $1,800 USD per year because of the Jones Act.

And now with the war in Ukraine, Hawaii can no longer rely on Russia, one of its top suppliers, for gas. So that $1,800 figure will become much higher for Hawaiians.

The Shorter the Trip, the More It Costs

For a long time, the financial impacts of the Jones Act only targeted residents of Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

But with inflation shooting up in the past 12 months and the supply-chain disruption from COVID-19, residents of the continental U.S. are beginning to feel the pinch, too.

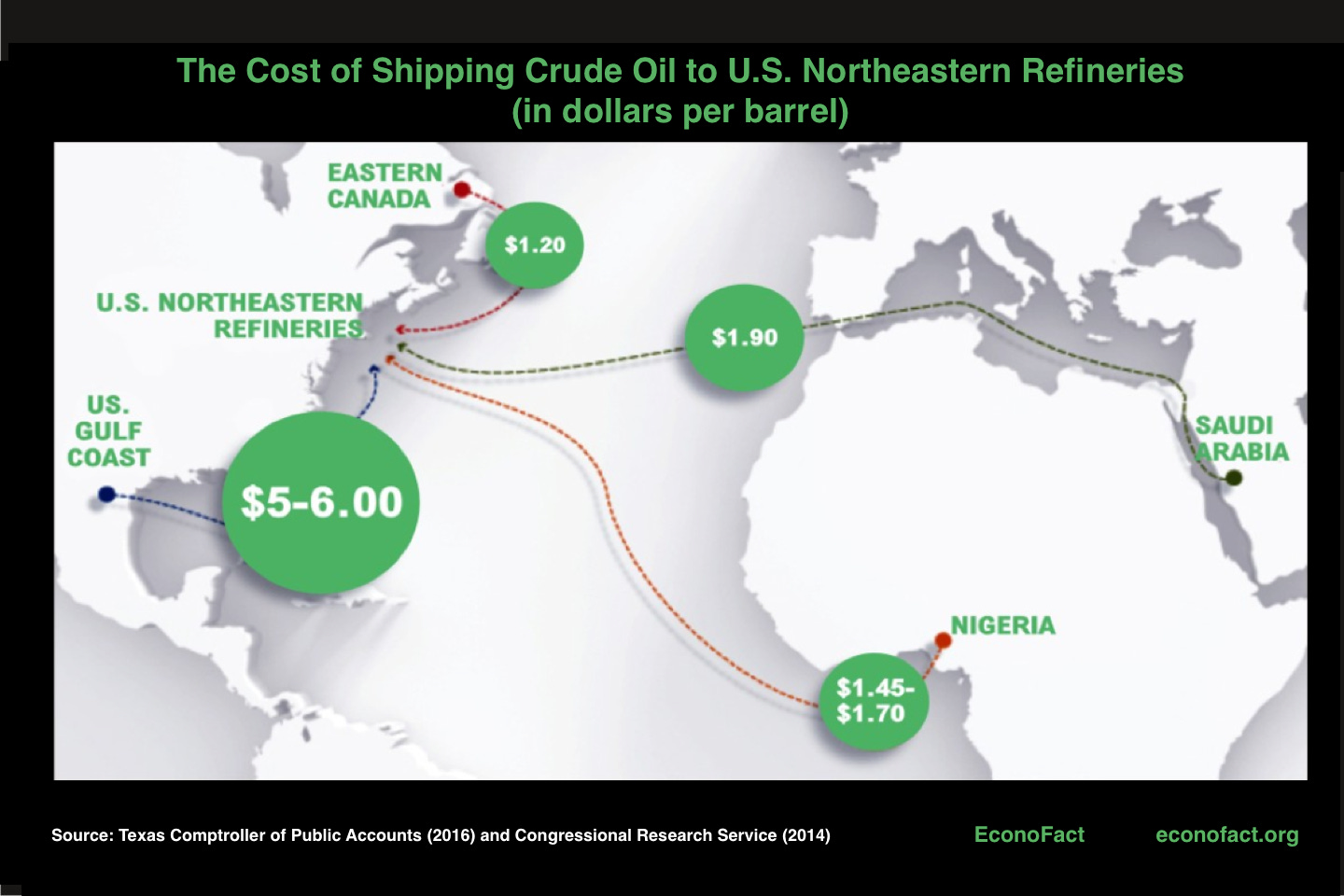

The next chart says it all.

Source: www.econofact.org

It costs $5 to $6 to ship a barrel of crude from Texas to the northeastern U.S. From Saudi Arabia or Nigeria, it only costs $1.45 to $1.90.

And just like in Puerto Rico and Hawaii, the Jones Act also increases the cost of daily staples in the continental U.S. as well.

Two independent studies concluded that the logistic cost of goods using railways is higher versus using a foreign-owned container ship to go between U.S. ports. The waterborne container costs about $0.80 USD per nautical mile (0.87 miles) while the same distance on a train will cost anywhere between $2.50 to $2.75 USD per mile.

This is due to domestic shipping companies artificially inflating their costs since the Jones Act undercuts any foreign competition.

The lack of efficiency from the absence of foreign competition means domestic shipping via water is a monopoly for the US maritime industry. They get to set the market price for shipping, charge a higher rate for shipbuilding/maintenance/operation, and dictate the terms for productivity.

This also drives up demand for alternative forms for logistics, such as trucking and railways and they get to charge a higher price as well because they are the only other alternatives.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found in their 2019 study that repealing the Jones Act would result in a gain up to $64 billion USD for the U.S. economy, because it would lead to reduced building costs for U.S. vessels.

Repeal or Reform?

As evidenced by the Fed’s speech and action, bringing down inflation is its number one priority.

The sooner inflation is under control, the sooner the Fed stops hiking interest rates. This is good news for risk-on assets. It will do wonders for the economy. Most asset classes will start to rally, including cryptocurrencies.

It is obvious that the Jones Act levies additional costs on U.S. consumers and adds on to the inflation problem that the FED is battling.

This price-gouging-in-disguise forces the American consumers to pay higher prices for their daily needs. Under the high-inflation environment we are seeing globally, we can use every bit of help we can get to fight high costs.

It can be eliminated.

But this is a perfect example that proves fighting inflation is not just the FED’s problem. This is also a legislative problem.

As indicated in Ben Lilly’s update from a few weeks ago, the FED is advocating for fiscal policy changes in addition to monetary policies to help combat inflation. And to do so in light of a declining growth rate for productivity.

However, with the end of globalization and the gradual shift to domestic manufacturing, the call for protectionism seems to get louder by the day. Under the broad umbrella of protecting national interests, the Jones Act won’t go away.

Also, with a faltering economy and no immediate relief in sight, it will be impossible for the Jones Act to be repealed because that would put thousands of people out of work.

Congress needs to step up and own this one.

What is needed is not an absolute abolition of the Jones Act, but a reform to modernize it. The goal should be to balance it as such that U.S. residents would not have to bear the unnecessary cost of an outdated and impractical century-old decree.

Hopefully we see this act discussed in the months comes given the high-inflation environment we currently are in.

Yours truly,

TD